DIGITAL AUDIO

Digital Music, or commonly known as digital audio, is a method of representing sound as numerical values. In contrast, analog systems like, magnetic tape, or vinyl records, rely on physical methods to reproduce the sound.

|

Download the Digital Audio Questions WORD doc and answer all questions.

You May Go to the QUIZLET site and find your class page. All answers are found under vocabulary terms 1-6 | ||||||

What is sound?

Sounds are pressure waves of air. If there wasn't any air, we wouldn't be able to hear sounds. There's no sound in space.

We hear sounds because our ears are sensitive to these pressure waves. Perhaps the easiest type of sound wave to understand is a short, sudden event like a clap. When you clap your hands, the air that was between your hands is pushed aside. This increases the air pressure in the space near your hands, because more air molecules are temporarily compressed into less space. The high pressure pushes the air molecules outwards in all directions at the speed of sound, which is about 340 meters per second. When the pressure wave reaches your ear, it pushes on your eardrum slightly, causing you to hear the clap.

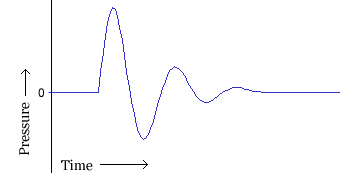

A hand clap is a short event that causes a single pressure wave that quickly dies out. The image above shows the waveform for a typical hand clap. In the waveform, the horizontal axis represents time, and the vertical axis is for pressure. The initial high pressure is followed by low pressure, but the oscillation quickly dies out.

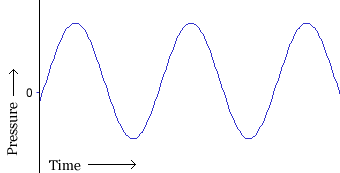

The other common type of sound wave is a periodic wave. When you ring a bell, after the initial strike (which is a little like a hand clap), the sound comes from the vibration of the bell. While the bell is still ringing, it vibrates at a particular frequency, depending on the size and shape of the bell, and this causes the nearby air to vibrate with the same frequency. This causes pressure waves of air to travel outwards from the bell, again at the speed of sound. Pressure waves from continuous vibration look more like this:

How is sound recorded?

A microphone consists of a small membrane that is free to vibrate, along with a mechanism that translates movements of the membrane into electrical signals. (The exact electrical mechanism varies depending on the type of microphone.) So acoustical waves are translated into electrical waves by the microphone. Typically, higher pressure corresponds to higher voltage, and vice versa.

A tape recorder translates the waveform yet again - this time from an electrical signal on a wire, to a magnetic signal on a tape. When you play a tape, the process gets performed in reverse, with the magnetic signal transforming into an electrical signal, and the electrical signal causing a speaker to vibrate, usually using an electromagnet.

How is sound recorded digitally?

In a digital recording system, sound is stored and manipulated as a stream of discrete numbers, each number representing the air pressure at a particular time. The numbers are generated by a microphone connected to a circuit called an ANALOG TO DIGITAL CONVERTER, or ADC.

Recording onto a tape is an example of analog recording. Audacity deals with digital recordings - recordings that have been sampled so that they can be used by a digital computer, like the one you're using now. Digital recording has a lot of benefits over analog recording. Digital files can be copied as many times as you want, with no loss in quality, and they can be burned to an audio CD or shared via the Internet. Digital audio files can also be edited much more easily than analog tapes.

The main device used in digital recording is a Analog-to-Digital Converter (ADC). The ADC captures a snapshot of the electric voltage on an audio line and represents it as a digital number that can be sent to a computer. By capturing the voltage thousands of times per second, you can get a very good approximation to the original audio signal:

Each dot in the figure above represents one audio sample. There are two factors that determine the quality of a digital recording:

Samples: The samples contain information telling your computer how the recorded signal sounded at certain instants in time. The more samples used to represent the signal, the better the quality of the recorded sound. For example, to make a digital audio recording that has the same quality as audio on a CD, the computer needs to receive 44,100 samples for every second of sound that's recorded.

1. Sample rate: The rate at which the samples are captured or played back, measured in Hertz (Hz), or samples per second. An audio CD has a sample rate of 44,100 Hz, often written as 44 KHz for short. This is also the default sample rate that Audacity uses, because audio CDs are so prevalent.

2. Sample format or sample size: Essentially this is the number of digits in the digital representation of each sample. Think of the sample rate as the horizontal precision of the digital waveform, and the sample format as the vertical precision. An audio CD has a precision of 16 bits, which corresponds to about 5 decimal digits.

Higher sampling rates allow a digital recording to accurately record higher frequencies of sound. The sampling rate should be at least twice the highest frequency you want to represent. Humans can't hear frequencies above about 20,000 Hz, so 44,100 Hz was chosen as the rate for audio CDs to just include all human frequencies. Sample rates of 96 and 192 KHz are starting to become more common, particularly in DVD-Audio, but many people honestly can't hear the difference.

Higher sample sizes allow for more dynamic range - louder louds and softer softs. If you are familiar with the decibel (dB) scale, the dynamic range on an audio CD is theoretically about 90 dB, but realistically signals that are -24 dB or more in volume are greatly reduced in quality. Audacity supports two additional sample sizes: 24-bit, which is commonly used in digital recording, and 32-bit float, which has almost infinite dynamic range, and only takes up twice as much storage as 16-bit samples.

Playback of digital audio uses a Digital-to-Analog Converter (DAC). This takes the sample and sets a certain voltage on the analog outputs to recreate the signal, that the Analog-to-Digital Converter originally took to create the sample. The DAC does this as faithfully as possible and the first CD players did only that, which didn't sound good at all. Nowadays DACs use Oversampling to smooth out the audio signal. The quality of the filters in the DAC also contribute to the quality of the recreated analog audio signal. The filter is part of a multitude of stages that make up a DAC.

How does audio get digitized on your computer?

Your computer has a soundcard - it could be a separate card, like a SoundBlaster, or it could be built-in to your computer. Either way, your soundcard comes with an Analog-to-Digital Converter (ADC) for recording, and a Digital-to-Analog Converter (DAC) for playing audio. Your operating system (Windows, Mac OS X, Linux, etc.) talks to the sound card to actually handle the recording and playback, and Audacity talks to your operating system so that you can capture sounds to a file, edit them, and mix multiple tracks while playing.

Waveform

Most people's introduction to audio on a computer will either be through a video editing program or a specific audio editing program. In most cases, the audio is represented in a way similar to below:

This particular waveform shows the two stereo channels, left on top and right on the bottom. Looking at the waveform we can see that there is a definite "beat" to the music here, which is actually a strong bass drum introduction to a music track. What the waveform is really showing is the volume of the music at time progresses; the larger the waveform, the louder the music. From this we can see that the initial drumbeat in the above example is louder than the following beats.

This method of displaying audio is a good way of representing how the audio plays in a visual way and closely matches how audio is stored in a normal uncompressed WAV file or on a CD. Uncompressed audio is stored as a sequence of numbers ("samples") that describe how loud each sample is. On a CD there are 44100 samples every second, so you can see that there are a lot of numbers to be stored for even short pieces of music.

Compression Formats

Lossless

UNCOMPRESSED

Audio File Preserves original data in the file

Larger File Size

Wav

AIFF

Lossy

Reduces file size significantly

Removes some data from the original file

MP3

AAC

WMA

File Formats

1. Audacity Project format (AUP)

|

4. MP3 (MPEG I, layer 3)

|

What is an MP3 file and how does it differ from WAV and AIFF files?

MP3 (MPEG II, layer 3) is a popular format for storing music and other audio. A typical MP3 file is one tenth the size of the original WAV or AIFF file, but it sounds very similar. MP3 encoders make use of psychoacoustic models to, in effect, "throw away" the parts of the sound that are very hard to hear, while leaving the loudest and most important parts alone.

Unfortunately, no MP3 encoder is perfect, and so an MP3 file will never sound quite as good as the original. Still, most people find that the quality of an MP3 file is virtually indistinguishable from a CD when played on headphones or on small computer speakers, which is why the format is so popular

MP3 (MPEG II, layer 3) is a popular format for storing music and other audio. A typical MP3 file is one tenth the size of the original WAV or AIFF file, but it sounds very similar. MP3 encoders make use of psychoacoustic models to, in effect, "throw away" the parts of the sound that are very hard to hear, while leaving the loudest and most important parts alone.

Unfortunately, no MP3 encoder is perfect, and so an MP3 file will never sound quite as good as the original. Still, most people find that the quality of an MP3 file is virtually indistinguishable from a CD when played on headphones or on small computer speakers, which is why the format is so popular

|

What is MP3?

MP3s (which stands for Moving Picture Experts Group, Layer 3) are digital audio files that are compressed to about 1/10 the size of a CD recording. Your computer compresses files by scanning them for repeating patterns of digits. It then replaces these patterns with smaller codes that take up less space. So, you can compress a CD song that has 50 megabytes of data into an MP3 that has only 4 or 5 megabytes (1 megabyte = 1,000,000 bytes; 1 byte = the size of 1 computer character, like the letter "a"). As a result, MP3s are compact enough to send over the Internet with little difference in sound quality. |

A Brief History. . . .

- The German company Fraunhofer-Gesellshaft developed MP3 technology and now licenses the patent rights to the audio compression technology - United States Patent 5,579,430 for a "digital encoding process". The inventors named on the MP3 patent are Bernhard Grill, Karl-Heinz Brandenburg, Thomas Sporer, Bernd Kurten, and Ernst Eberlein.

- In 1987, the prestigious Fraunhofer Institut Integrierte Schaltungen research center (part of Fraunhofer Gesellschaft) began researching high quality, low bit-rate audio coding, a project named EUREKA project EU147, Digital Audio Broadcasting (DAB).

- Two names are mentioned most frequently in connection with the development of MP3. The Fraunhofer Institut was helped with their audio coding by Dieter Seitzer, a professor at the University of Erlangen. Dieter Seitzer had been working on the quality transfer of music over a standard phone line. The Fraunhofer research was led by Karlheinz Brandenburg often called the "father of MP3". Karlheinz Brandenburg was a specialist in mathematics and electronics and had been researching methods of compressing music since 1977. In an interview with Intel, Karlheinz Brandenburg described how MP3 took several years to fully develop and almost failed. Brandenburg stated "In 1991, the project almost died. During modification tests, the encoding simply did not want to work properly. Two days before submission of the first version of the MP3 codec, we found the compiler error."

- In 1997, 18-year-old Justin Frankel of Sedona, Arizona, created the first popular MP3 player. Called Winamp, the player is a computer program that converts MP3 audio (sound) files from computer numbers or digits into sound waves you hear through your computer's speakers. Today, listening to MP3s is so widespread, the most common word used on all Internet search engines (sites that find Web pages to match words you type in) is "MP3." And Frankel, a mere 20 years old, is a multimillionaire!

MP3 MYTHS

There seems to be a great deal of confusion about what is, or is not, legal regarding music these days. People don’t seem to know where the line is between enjoying music from an artist or band that they like, or violating the copyright protection of that same music. Below is a list of common myths associated with buying, sharing and listening to digital music and what the realities are.

Recording Industry Association of America

Myth No. 1: The RIAA will sue you for downloading music.

As I mentioned in a previous column, the RIAA is currently suing only users who share more than 1,000 songs. This doesn't mean that it is legal to download copyrighted music without permission of the copyright owner. It's not (see below). At this time, however, it appears that the RIAA is not targeting people who download copyrighted music. They are going after uploaders, not downloaders, which means that as long as you aren't sharing a significant number of files, the ongoing purge will pass you by.

Myth No. 2: Downloading songs for free from the Internet is fine.

Unfortunately, with very few exceptions, this is untrue. The songs are copyright protected and the owner of the copyright is owed compensation for the song. If you find music on the Internet for free, the individual or business sharing the music is most likely violating the law and if you download the song without paying for it you will be stealing.

Myth No. 3: Downloading copyrighted material without permission is legal.

In the interest of fairness, I must point out that downloading copyrighted material without permission is 100 percent illegal. When you download an MP3, you make a copy of that file from a remote location onto your hard drive. Copying the song is the exclusive right of the copyright holder, and doing so without permission is an act of copyright infringement.

Myth No. 4: I can share my music with friends because I own the CD

The fact that you purchased a CD entitles you to listen to the music all you want, but not to share that privilege with others. You can make a copy of the CD for yourself in case you damage or lose the original. You can rip the music from the CD onto your computer or laptop and convert the music to MP3 or WMA or other formats and listen to it on portable MP3 players or other devices. Your purchase of the music entitles you to listen to it pretty much any way you want, but you can’t give copies of it to friends or family. I am not suggesting that you can't *play* the music when other people are around, but that you can't give them a copy of the music, in any format, to take with them when they leave.

Myth No. 5: Its OK though, because I gave my friend the original CD

You can sell or give away the original CD, but only as long as you no longer have any copies of the music in any format (unless of course you have another copy that has been legitimately paid for). You can not copy the CD onto your computer and load MP3’s of it onto your portable MP3 player, and then give the original CD to your best friend because you don’t need it any more.

Think of it like you bought a couch. You can use the couch in your living room if you want. You can move it to a bedroom if it works better for you there. You can remove the throw pillows and use them in a different room than the couch. But, when you give the couch to your friend, the couch is gone. You can’t *both* give the couch away *and* keep the couch at the same time, and the music that you buy should be treated the same way.

Myth No 6: It isn’t “stealing” because I wasn’t going to pay for it anyway

Some people feel that because they would never actually spend the money to buy the CD, illegally copying or downloading it from somewhere else really isn’t costing the artist or the industry any money. Along these same lines, some people may copy or download music to try and decide if they like it enough to buy it, and just never get around to buying it. However, sites like Amazon.com now have clips or samples available to listen to of virtually every song on every CD available. Rather than crossing the ethical line, you should just visit a site like this and play the clips to help you make your purchasing decision. In the end, you may very well find that you would rather buy just one or two songs for $1 each rather than spending $15 for a CD filled mostly with music you don’t care for.

There seems to be a great deal of confusion about what is, or is not, legal regarding music these days. People don’t seem to know where the line is between enjoying music from an artist or band that they like, or violating the copyright protection of that same music. Below is a list of common myths associated with buying, sharing and listening to digital music and what the realities are.

Recording Industry Association of America

Myth No. 1: The RIAA will sue you for downloading music.

As I mentioned in a previous column, the RIAA is currently suing only users who share more than 1,000 songs. This doesn't mean that it is legal to download copyrighted music without permission of the copyright owner. It's not (see below). At this time, however, it appears that the RIAA is not targeting people who download copyrighted music. They are going after uploaders, not downloaders, which means that as long as you aren't sharing a significant number of files, the ongoing purge will pass you by.

Myth No. 2: Downloading songs for free from the Internet is fine.

Unfortunately, with very few exceptions, this is untrue. The songs are copyright protected and the owner of the copyright is owed compensation for the song. If you find music on the Internet for free, the individual or business sharing the music is most likely violating the law and if you download the song without paying for it you will be stealing.

Myth No. 3: Downloading copyrighted material without permission is legal.

In the interest of fairness, I must point out that downloading copyrighted material without permission is 100 percent illegal. When you download an MP3, you make a copy of that file from a remote location onto your hard drive. Copying the song is the exclusive right of the copyright holder, and doing so without permission is an act of copyright infringement.

Myth No. 4: I can share my music with friends because I own the CD

The fact that you purchased a CD entitles you to listen to the music all you want, but not to share that privilege with others. You can make a copy of the CD for yourself in case you damage or lose the original. You can rip the music from the CD onto your computer or laptop and convert the music to MP3 or WMA or other formats and listen to it on portable MP3 players or other devices. Your purchase of the music entitles you to listen to it pretty much any way you want, but you can’t give copies of it to friends or family. I am not suggesting that you can't *play* the music when other people are around, but that you can't give them a copy of the music, in any format, to take with them when they leave.

Myth No. 5: Its OK though, because I gave my friend the original CD

You can sell or give away the original CD, but only as long as you no longer have any copies of the music in any format (unless of course you have another copy that has been legitimately paid for). You can not copy the CD onto your computer and load MP3’s of it onto your portable MP3 player, and then give the original CD to your best friend because you don’t need it any more.

Think of it like you bought a couch. You can use the couch in your living room if you want. You can move it to a bedroom if it works better for you there. You can remove the throw pillows and use them in a different room than the couch. But, when you give the couch to your friend, the couch is gone. You can’t *both* give the couch away *and* keep the couch at the same time, and the music that you buy should be treated the same way.

Myth No 6: It isn’t “stealing” because I wasn’t going to pay for it anyway

Some people feel that because they would never actually spend the money to buy the CD, illegally copying or downloading it from somewhere else really isn’t costing the artist or the industry any money. Along these same lines, some people may copy or download music to try and decide if they like it enough to buy it, and just never get around to buying it. However, sites like Amazon.com now have clips or samples available to listen to of virtually every song on every CD available. Rather than crossing the ethical line, you should just visit a site like this and play the clips to help you make your purchasing decision. In the end, you may very well find that you would rather buy just one or two songs for $1 each rather than spending $15 for a CD filled mostly with music you don’t care for.